Chinese Dishes You Can’t Truly Taste Anywhere But China (Trust a Traveling Foodie’s 10+ Year Quest)

Let me start with a confession: I’ve chased “authentic Chinese food” in 12 countries across Europe and North America. I’ve sat in restaurants with red lanterns and fake calligraphy, ordered dishes with names that sounded familiar… and left every time thinking, “This is close, but not it.”

Here’s the thing: Chinese cuisine isn’t just ingredients and recipes—it’s the street-side chaos, the regional water, the grandma’s secret spice ratios, and the way locals eat it (standing up at a stall at 7 a.m., or huddled over a hot pot till midnight). After 10+ years of road-tripping China’s food lanes, these 17 dishes are the ones that only hit different on their home turf.

1. Chongqing Hot Pot: The Numbing, Spicy Heartbeat of the City

I once tried a “Chongqing hot pot” in London that used pre-made chili paste from a jar. Spoiler: It didn’t make my lips tingle for an hour (the good kind of tingle). In Chongqing, the soup base is non-negotiable: Sichuan peppercorns (the star of the show), dried chilies, and a secret blend of spices simmered for hours in beef or pork bone broth. The streets smell like it before you even see the stalls—tiny holes-in-the-wall where plastic stools crowd the sidewalk, and every table has a pot bubbling so fiercely it looks like it might boil over. Locals don’t just eat it—they communalize it. You’ll share plates of beef belly, lotus root slices, and “chongqing noodles” (yes, they double down) with strangers at the next table. And no matter if it’s 35°C (95°F) in summer or freezing in winter? The restaurants are packed. Pro tip: Pair it with local beer and a side of pickled radish to cut the heat (you’ll need it).

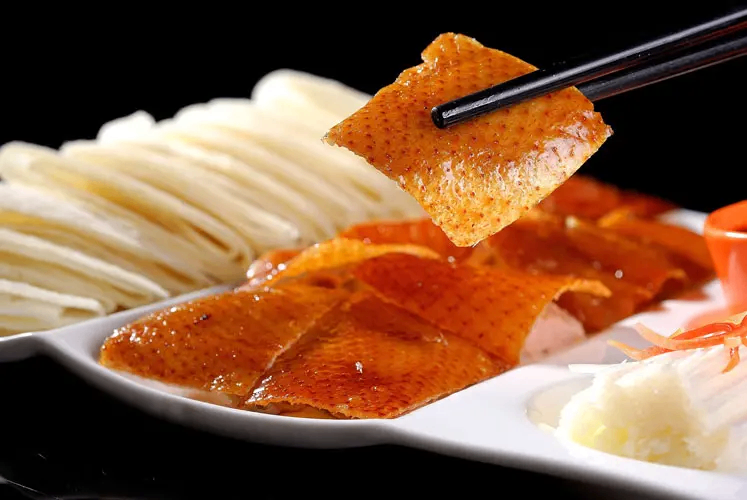

2. Beijing Roast Duck: It’s All About the Wood (and the Ritual)

Every tourist knows Quanjude (founded in 1864—130+ years of duck expertise), but I learned the real secret from a local cab driver: the fruitwood. In Beijing, they roast the ducks over pear or jujube wood, which infuses the skin with a sweet, smoky aroma you can’t replicate with gas or electric ovens. The duck skin should be so crispy it cracks when you touch it, and the meat is fatty but not greasy—never dry. The ritual matters too: wrapping it in a thin pancake with hoisin sauce, scallions, and cucumber, then popping the whole thing in your mouth in one bite. I’ve seen tourists try to “save room” by splitting a pancake—big mistake.

3. Lanzhou Beef Noodles: The “Clear Soup” That’s Anything But Basic

You’ll find “Lanzhou noodles” in every Chinese city, but true Lanzhou beef noodles? They’re a masterclass in simplicity. The broth is simmered for 8+ hours with beef bones, ginger, and star anise—no heavy spices, just pure, clean umami. The noodles are hand-pulled to order: chefs twist and stretch the dough into thin strands (or thick, chewy ones if you ask) right in front of you. The beef is tender, the soup is seasoned with just a pinch of salt and white pepper, and locals eat it standing up at street stalls for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I once waited 20 minutes in a line of 50 people for a bowl in Lanzhou’s old town. Worth every second.

4. Wuhan Hot Dry Noodles: The Greasy, Savory Breakfast That Defines the City

Wake up in Wuhan at 6 a.m., and the streets are already filled with vendors stirring big pots of noodles. Hot dry noodles (or reganmian) aren’t soupy—they’re tossed in sesame paste, soy sauce, garlic, and a drizzle of chili oil, with a sprinkle of scallions and pickled radish. The magic is in the oil: locals use a specific type of sesame paste that’s thicker and nuttier than what’s exported, and the noodles are cooked al dente so they cling to the sauce. I made the mistake of eating one without a drink my first time—my mouth was so dry I chugged a bottle of local soybean milk in 10 seconds. Pro move: Pair it with a cup of doujiang (soy milk) or a fried dough stick (youtiao).

5. Xi’an Yangrou Paomo: Tear the Bread, Sip the Broth

Xi’an is the home of ancient city walls and yangrou paomo—lamb stew with torn flatbread that’s equal parts messy and comforting. The rules are strict: you tear the bread into tiny pieces (the smaller, the better—locals will judge you if they’re too big) and hand it to the chef, who boils it in lamb broth with tender chunks of lamb. It’s served with pickled garlic and chili sauce, and you eat it with a spoon and chopsticks—sip the broth, chew the bread-soaked-in-lamb-goodness, and bite into a piece of garlic to balance the richness. I ate it on a freezing day in Xi’an’s Muslim Quarter, sitting on a stool next to an elder who taught me how to tear the bread “properly.”

6. Xi’an Rou Jia Mo: China’s OG “Hamburger” (Way Better Than Fast Food)

Let’s get one thing straight: a rou jia mo from a Xi’an street stall is not a hamburger—it’s a cultural icon. The bun is baked in a clay oven until it’s crispy on the outside and soft inside, and the filling is pork (or lamb) braised for hours in star anise, cinnamon, and soy sauce until it’s fall-apart tender. Locals grab them on their way to work, holding the bun with a napkin to catch the juice. I’ve tried versions in New York that used store-bought buns and pre-cooked meat—no comparison. The Xi’an version has that “slow-cooked by grandma” flavor you can’t rush.

7. Chongqing Small Noodles: The Breakfast That Hits Harder Than Coffee

Chongqing loves its noodles so much, they have two iconic dishes (hot pot and this). Chongqing small noodles (chongqing xiaomian) are a soup noodle that’s all about the sauce: scallions, garlic, chili oil, soy sauce, vinegar, and a dollop of beef or pork mince. The broth is light, but the sauce is bold—spicy, savory, and a little tangy. Locals line up at stalls at 6 a.m. for this, standing up to slurp noodles while checking their phones. I once had three bowls in one day (don’t judge—they’re addictive).

8. Liuzhou Snail Noodles: The “Acquired Taste” That’s a Obsession

If you’ve never smelled luosifen (snail noodles), you’re in for a surprise—it’s pungent, sour, and a little funky (thanks to the pickled bamboo shoots). But in Liuzhou, Guangxi, it’s a way of life. The soup is simmered with snails, pork bones, and a blend of spices for hours, giving it a rich, umami base that balances the sour bamboo shoots and spicy chili oil. Add in chewy rice noodles, fried peanuts, tofu sticks, and a boiled egg, and you’ve got a bowl that’s sour, spicy, salty, and sweet all at once. I saw a college student in Liuzhou eat three bowls in a row at a campus stall. When I asked why, he said, “It’s like comfort food, but with a kick.” Fair.

9. Guilin Rice Noodles: The Gravy That Makes the Dish

Guilin’s rice noodles are a morning staple, but the secret isn’t the noodles—it’s the gravy. Locals use a slow-cooked pork or beef gravy that’s thick and savory, poured over fresh rice noodles with a sprinkle of fried soybeans, scallions, and pickled bamboo. You can customize it with chili oil or vinegar, but the best way to eat it is “dry” (no broth) with a side of bone soup to sip. I ate this every morning for a week in Guilin, and by day 3, the vendor was already handing me my bowl before I ordered.

10. Tianjin Goubuli Steamed Buns: 160+ Years of Juicy Perfection

Goubuli (founded in 1858) isn’t just a brand—it’s a legend. The story goes that the founder was a boy named “Gou” (dog) who was so quiet, people called him “Gou Bu Li” (Dog Doesn’t Care). His buns, though? People cared—a lot. The buns have 18 pleats (a tradition you’ll see chefs count as they fold), and the filling is pork with a secret blend of spices, mixed with broth that turns to jelly when chilled—so when you bite into a hot bun, the juice bursts out (watch your shirt). They’ve got 100+ varieties now (seafood, wild vegetable, whole crab), but the classic pork bun is still the best.

11. Shanghai Pan-Fried Buns: The “Soup” Inside the Bun

Shanghai’s shengjian mantou (pan-fried buns) are a game-changer. The bottom is golden and crispy, the top is soft and fluffy, and inside? A juicy pork filling with a splash of broth that’s been gelled and folded in (another “jelly to soup” trick). Locals eat them with a spoon to catch the juice, and the best stalls are the ones where the chef yells orders while flipping buns in a giant pan. I once burned my tongue on one because I was too eager to take a bite—worth it for that first burst of savory broth. Pro tip: Dip them in black vinegar and ginger sauce to cut the richness.

12. Hunan Chopped Chili Fish Head: Spicy, Sour, and Bold

Hunan cuisine is for people who love heat (the tangy kind, not just numbing). Chopped chili fish head is the star: a whole fish head (usually carp or grass carp) covered in homemade chopped chilies, steamed with ginger, garlic, and soy sauce until the flesh is flaky and the sauce soaks into every crevice. In Hunan, every restaurant serves this—from fancy places to street stalls—and it’s meant to be shared (with rice, lots of rice). I ate it with a local family in Changsha, and they laughed when I wiped my eyes from the spice: “You’re not a real Hunan eater till you cry and ask for more.”

13. Xinjiang Big Plate Chicken: The Hearty, Spicy Comfort of the Northwest

Big plate chicken (da pan ji) was born in Xinjiang’s roadside restaurants in the 1980s, and it’s still a staple for truck drivers and travelers. It’s a one-pot wonder: chicken stir-fried with dried chilies, potatoes, and bell peppers, then stewed until the potatoes are soft and the sauce is thick and spicy. The best part? They serve it with wide noodles that you toss in the leftover sauce—chewy, spicy, and so filling you’ll skip dinner. I ate this in a tiny restaurant on the way to the Tian Shan mountains, and the chef added extra chili just for me (I regretted it, but also didn’t).

14. Cantonese Char Siu Buns: The “Flowering” Bun That Smells Like Home

Cantonese dim sum isn’t the same outside of Guangdong—but char siu buns (cha siu bao) are the biggest offender. The authentic ones are “flowering” buns: the top cracks open when steamed, revealing a sweet, savory char siu filling (pork marinated in honey, soy sauce, and five-spice). The bun skin is soft and fluffy, and the filling has just the right balance of fat and lean meat. I’ve had versions in Hong Kong (yes, it counts—Guangdong’s next door) that smelled like char siu before I even opened the basket. The best stalls are in old dim sum houses where the chefs have been making them for 30+ years.

15. Guizhou Sour Soup Fish: The Fermented Chili That Makes It Unique

Guizhou loves sour food—loves it. Sour soup fish (suan tang yu) is a Miao ethnic group specialty, and the soup is the star: fermented chili paste (made with local chilies and rice) simmered with fish bones, ginger, and Chinese herbs. The fish is fresh (usually carp or catfish) and cooked whole in the soup, so it soaks up every bit of sour, spicy flavor. Add soybean sprouts, bamboo shoots, and scallions, and you’ve got a bowl that’s tangy, spicy, and comforting all at once. I ate this in a Miao village outside Guiyang, and the grandma who made it told me the fermented chili was 3 years old—“the older, the better.”

16. Sichuan Chuan Chuan Xiang: The “Little Hot Pot” for Solo Eaters

Chuan chuan xiang (skewer hot pot) is Sichuan’s answer to solo dining: tiny bamboo skewers with everything from beef to tofu to lotus root, cooked in a pot of spicy or bone broth. It’s cheaper than hot pot, more casual, and perfect for eating alone (or with friends—you just count the skewers at the end). In Chengdu, the streets are lined with chuan chuan stalls where you can pick your skewers from a giant cooler, then dip them in a sesame paste sauce after cooking. I once spent an hour there, trying every skewer I could find, and the bill was less than $5.

17. Hangzhou Dongpo Pork: The Sweet, Savory Pork That’s Fit for a Poet

Dongpo pork is named after Su Dongpo, a Song Dynasty poet who loved cooking (relatable). In Hangzhou, it’s made with pork belly (half fat, half lean) braised in yellow rice wine and rock sugar for hours, until the fat melts into the meat and the sauce is thick and sweet. It’s oily but not greasy— the rice wine cuts through the richness, and the meat is so tender it falls apart with a fork. I ate this in a restaurant overlooking West Lake, and the waiter told me the recipe hasn’t changed in 900 years. “Su Dongpo would approve,” he said. I believe him.

Why These Dishes Only Taste Right in China

At the end of the day, it’s not just the ingredients—it’s the context. It’s eating hot dry noodles while watching Wuhan’s morning rush, or sharing a hot pot with Chongqing locals who don’t speak your language but pass you a beer anyway. It’s the street-side smoke, the regional water that changes the broth’s flavor, and the grandma who adds an extra spoonful of chili because she thinks you need it. I’ve brought back spices, recipes, and even a Lanzhou noodle-making kit to my home country. None of it’s ever been the same. If you want the real deal? You’ve got to go to the source.

Have you ever tried a “authentic” Chinese dish abroad that missed the mark? Or a local Chinese dish that blew your mind? Drop a comment—I’d love to hear your food stories!

Questions?

-

Email

zhanwenjuan@lingshicha.net

-

WhatsApp